Where the New Jersey Meadowlands inspire a sense of doom, the Ivy landfill near Charlottesville, Virginia, is its very opposite, with its 350 acres of wholesomeness, optimism, and can-do spirit, seasoned with a herd of deer and a mountain lion stalking their steps in fauning season. Even if 87 of those acres are covered in garbage buboes.

Ivy Landfill, Covered with Snow

It doesn’t hurt that it’s so pretty out here, garbage and all. Overwhelmed by mountains, a vast temperate rain forest quietly biding its time, virgin snow and deep-blue sky, a measly little PVC pipe sticking up out of the earth here and there seems a minor thing. Even if it’s going to take 30 to 50 years for that pipe to become unnecessary—at the current best guess of sanitary engineers—it just doesn’t look like the end of the world. Outlook, it seems, has a good deal to do with the view.

Ivy’s operations manager, Mark Brownlee, a mild man in his late fifties or early sixties with a very red nose, kind eyes, and a musical southern twang, took me around. After an awkward start and the usual suspicious/incredulous questions (“What program is this for? Who are you with?”), he became pretty straightforward.

Ivy got its start in life in the 70s, as Charlottesville’s city dump, before the introduction of current landfill regulations. Later the landfill also accepted waste from other communities in Albemarle county. When I lived in Charlottesville, in the spring of 1990, I did my best to help it grow–albeit in blissfull ignorance of what happened to my stuff after I gave it up for adoption, once a week. It seems I’m partially responsible for the bubo to the left of the road in the picture above, since Mark told me the bubo to the right contains only construction and demolition debris. I remember arguing with my husband over who should take out the trash, but I have absolutely no recollection of thinking about my garbage, ever once, beyond its short trip to the curb. Of course, I don’t. I had better things to do, back then, than worry about what happens to my garbage.

Garbage Transfer, Front Row Seating Provided

In 2001, the landfill closed. A layer of clay icing has been added on top. Pipes stick up everywhere like birthday candles. Mark allows as how the Rivanna Waste Authority, which he embodies, has to be vigilant and inventive, to make sure the landfill doesn’t come to haunt its upscale neighbors, like Freud’s return of the repressed. So methane is monitored, captured, and flared off. Leachate is collected and trucked to a treatment plant. Bacteria are injected into the landfill, in the hope that they will neutralize harmful substances. Volatile organic compounds are extracted by the shiny new soil vapor extraction machine, one of the very first to be installed, according to Mark.

Residents can deliver recyclables, including cell phones and paint, newspaper and cardboard, as well as reusable items, among which, remarkably, is a huge contingent of exercise equipment, good intentions gone to waste.

The Edge of the Magic Mountain

All the while, the upscale neighbors are kept informed of all developments with an unusual spirit of openness. That’s what impresses me most: this simple willingness to lift the veil. It compares exceedingly well with the more usual response, which is to come running with loud protests and write down my license plate number if I take a picture of the outside area of a landfill.

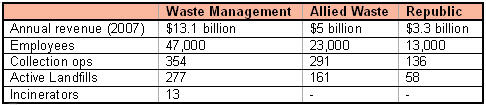

And in the meantime, the garbage still arrives, in its never-ending way. It goes from the garbage truck onto the conveyer into another truck, and then off to a Waste Management landfill just outside of Jetersville, Virginia, a mere bump on the map which doesn’t seem to have a whole lot going for it besides space for everybody’s else trash.