The United States may have as many as 100,00 landfills, large and small. A significant proportion of them doesn’t have a liner.

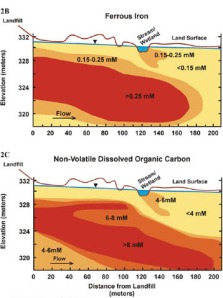

Contaminants from landfill leach into groundwater in unsavory plumes containing heavy metals, chlorinated compounds, and hospital germs, to mention just a few of the ingredients. Take Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island, which is built in a tidal swamp. The tides wash into its bed unhampered and wash out leachate, an estimated 3 million liters of it every day (which is almost 800,000 gallons). Under certain conditions, some of the contaminants from landfill may be cleaned up by naturally occurring processes, as a study at the Norman, Oklahoma, landfill has shown. but not nearly all of them. Moreover, it takes time.

In addition to leachate, landfills release methane, which is created when organics decompose when there is no oxygen and which contributes heavily to global warming. In fact, landfill methane is thought to account for about 5% of the total annual increase in “radiative force” that lies behind the greenhouse effect. In other words, the adverse effects of landfill are both local and global. Back to Fresh Kills for a moment: according to a 1998 estimate, it releases 2,650 tons of methane a day. Perhaps that number is reduced somewhat since dumping stopped (in 2001), but it can’t be by much. After all, the garbage is still there quietly percolating under the skin of dirt that covers it up.

How long it takes for a dump to stop being a source of pollution is not yet known. Under normal conditions, most organic materials will decompose to clays and other natural substances in about 30 years. But in landfills, conditions are not normal. The stuff is packed in so tight that not enough air and water gets to it for the decomposition to proceed apace, in part because these huge piles we build cocoon much of the trash inside them, in part because sanitary engineers try to halt the decomposition process to prevent leaks.

On the whole, then, there’s not enough air and water to speed along biodegration, too much air and water to prevent contamination and outgassing.

The serious environmental impact of landfilling our waste was not fully recognized until the 1970s, when the EPA began to insist on an engineering standard to contain leachate and methane, at least to some extent. All the same, the EPA recognizes that no liner is equal to the environmental stresses to which it will likely be subjected over its lifetime. Sooner or later, that leachate plume will emerge. And no methane collection system comes close to capturing all the gas generated in our trash heaps.

In the decades after the EPA established regulations, many of the older unlined, unengineered dumps were closed. In some cases, remediation systems were subsequently put in place. Most dumps, however, were simply taken out of operation and covered up. I’m sure it’s a good thing to stop adding to the problem, but closing a landfill to new arrivals doesn’t in any way mean that current occupants are no longer leaving. “Closed” really isn’t quite the word for a landfill at which the garbage trucks have stopped coming. Neither is “inactive.”

A few of the very worst landfills have been cleaned up, such as the infamous Love Canal dump in Niagara Falls. Much depends, it seems, on local activists. In other cases, cleanup is really unimaginable. Think of Fresh Kills again, which contains 67,000,000 cubic meters of compacted trash in four mountains spreading over 12 hectares of land (or 2,366,082,670 cubic feet spread out over 2200 acres). Perhaps we can expect improved containment systems in the future, but cleanup is hardly in the cards for a country that has squandered much of its wealth in the pursuit of ever greater riches.

Why exactly do we have landfills if they are so bad? Why are new landfills still being made?

It’s not that there is no alternative. In Germany and the Netherlands, for example, all non-recyclable, non-hazardous waste is burned. In 40 years of heavy reliance on incineration, there have been no environmental disasters. From what I can understand, incinerators don’t scrub every last pollutant out of the exhaust gases, but their overall environmental impact is considerably less severe than the cumulative effect of landfill when considered over the entire life of the garbage.

From all my reading on the subject, I can distill only two reasons why landfilling is still standard practice in this country, despite severe environmental consequences:

> Space is still cheap, and landfills are relatively simple to build, requiring modest upfront capital investment, even now that more engineering is required.

> The environmental movement has organized very aggressively against incineration. In Fat of the Land, Ben Miller explains that environmental organizations feared that incineration would stand in the way of recycling. They scared people half to death with the notion of toxic ashes left over after combustion, and all over the country they turned out crowds to protest very effectively. Too bad if it was under false pretenses. Incinerator ash doesn’t contain any toxins that aren’t to be found in the dump. Burning doesn’t create toxins, although of course it does get rid of biohazards. Ash is significantly more stable than household garbage.

Of course this is not to say that every incinerator necessarily runs as it’s meant to. The Northwest incinerator in Chicago, which has devoured some of my own trash, seems to have been in violation of safety standards much of the time.

If Miller’s supposition is true, it’s a sad chapter in the history of the environmental movement. Here we are, 30 years later, with a handfull of incinerators, 100,000 leaky landfills, and 100,000 plumes, large and small. , a mere handfull of incinerators (a few of them them–I will say this–perpetually in violation of safety standards, such as the Northwest incinerator in Chicago), and no recycling yet in lots of places.

Fortunately, new developments are underfoot. With the rising price of oil, the larger landfills have started turning captured methane into usable fuel. There are experiments with bioreactor landfill, in which the trash is treated to decompose faster and release more methane (for fuel) under more controlled circumstances. A new generation of incinerators is being built, which would burn garbage at higher temperatures, posing even less environmental risk. I’ve heard they can mine old landfills for fuel, which would mean that some of those 100,000 could perhaps finally disappear.

More on Fresh Kills:

– love letters and cabbage leaves

More about trash in Chicago: